Lucy Wood reports…

The results of this spring’s week-long Big River Watch will create the current picture of river health.

ORGANISED by The Rivers Trust twice a year, the most recent week-long watch between April 25 and May 1 saw 3900 members of the public download a special app, visit their local river, and spend a few moments recording what they saw and how they felt. The participants completed 2300 individual surveys, which equals to 41 days spent river-watching.

Wildlife spotted included coots, beavers, dippers, dragonflies, ducks, fish, herons, kingfishers, riverflies, moorhens, rats, otters and swans, while pollution sighted included silt, livestock, sewage and sewage fungus, and road run-off. When asked to record their impressions of the river they were surveying, 70% reported ‘healthy,’ while only 22% reported ‘unhealthy’ and 8% ‘other.’

The results have been recorded by The Rivers Trust and will be used in comparison to other surveys to monitor the health of our rivers.

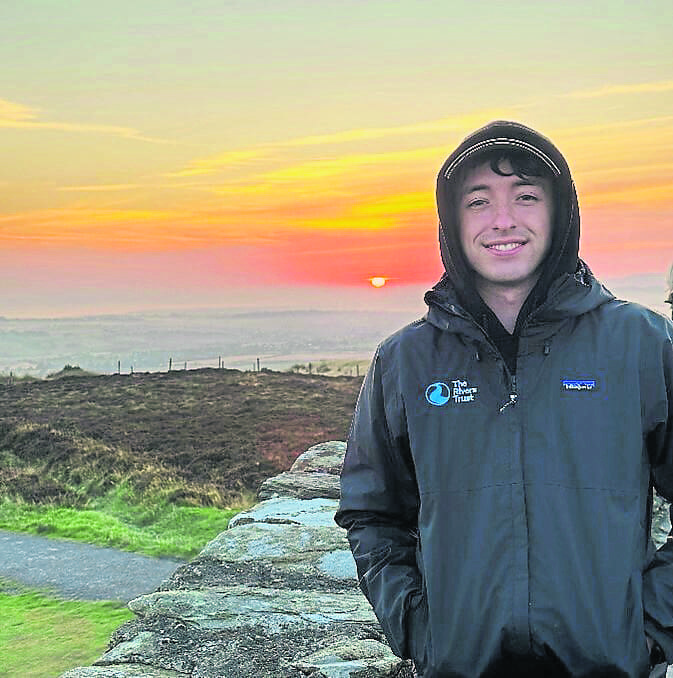

Barry McLaughlin, a project manager at the trust, writing a blog on its website about this most recent survey, said: “Rivers and wetlands are the lifeblood of our landscapes, supporting diverse wildlife and providing essential ecosystem services. Yet human-induced impacts such as climate change and pollution pose serious threats to these amazing ecosystems. This is what makes the Big River Watch so important – empowering people to take an active role in monitoring and protecting their local rivers and wetlands, providing valuable data that can shape conservation efforts.

“I grew up on Inch, a small rural island along the Donegal coast, home to Ireland’s largest wildfowl reserve, Inch Wildfowl Reserve. My childhood was spent exploring the great outdoors, where adventures turned nature into my classroom. I have fond memories of rustling through reeds in camo gear with binoculars, searching for a smew or bittern, wading knee-deep in bogs to find frogs and newts, or fishing along the riverbanks with my dad. Every moment spent near wetlands deepened my appreciation for wildlife and conservation.

“Participating in the Big River Watch and other citizen science projects encourages people to observe and learn from their rivers and wildlife. It’s an opportunity to meet friends, discover new interests, relax, practice mindfulness, and contribute to vital conservation efforts. For some, it can even spark a lifelong passion or career like me.

“Last year, I participated in the Big River Watch around Inch Lake and its surrounding rivers and wetlands, except I took a slightly different approach. Instead of traditional observation, I used trail cameras to capture the rich ecosystem in action, revealing the hidden world along the water’s edge.

“Trail cameras are an excellent tool for wildlife observation, especially in areas where human presence might disturb natural behaviour. Placing a camera along wetlands for round-the-clock monitoring, capturing images and videos of species that might otherwise go unnoticed. By participating in the Big River Watch, I’ve gained a deeper insight into the interconnectedness of ecosystems. Trail camera footage not only serves as a tool for observation but also raises awareness of the importance of conservation. The data collected contributes to broader efforts in protecting our rivers, ensuring they remain thriving habitats for future generations.”

You can watch Barry’s footage on his Instagram account, @barrymclaughlin_wildlife

The Big River Watch runs twice a year; for more information about it and to take part in the next one, visit https://theriverstrust.org/take-action/the-big-river-watchrust