In this first instalment, Tim Coghlan recalls the life and works, and his own personal memories, of canal artist Alan Firth (1933-2012), once described by the IWA as ‘probably Britian’s best-known waterways artist.’

THERE is one signature painting by Alan Firth which really has most of the elements of his canal artist style, technique and artistic licence. It is his well-known painting of Bearley Lock on the South Stratford Canal. The high-rising lock, lying alone and isolated in the middle of the countryside a half-mile north of the Edstone Aqueduct, is the only one on that canal which is not linked to a lock flight, and with it a barrel-shaped lock keeper’s cottage. Regardless of its correct name, it was just known to the working boatmen as Odd Lock. Alan Firth was also a loner, and the Odd Lock name had its appeal. As Terry Stroud, the main distributor of his works, commented to me following his death: “I probably sold more of his works than anyone else, and met up with him on a number of occasions, but I really knew very little about him as a person.”

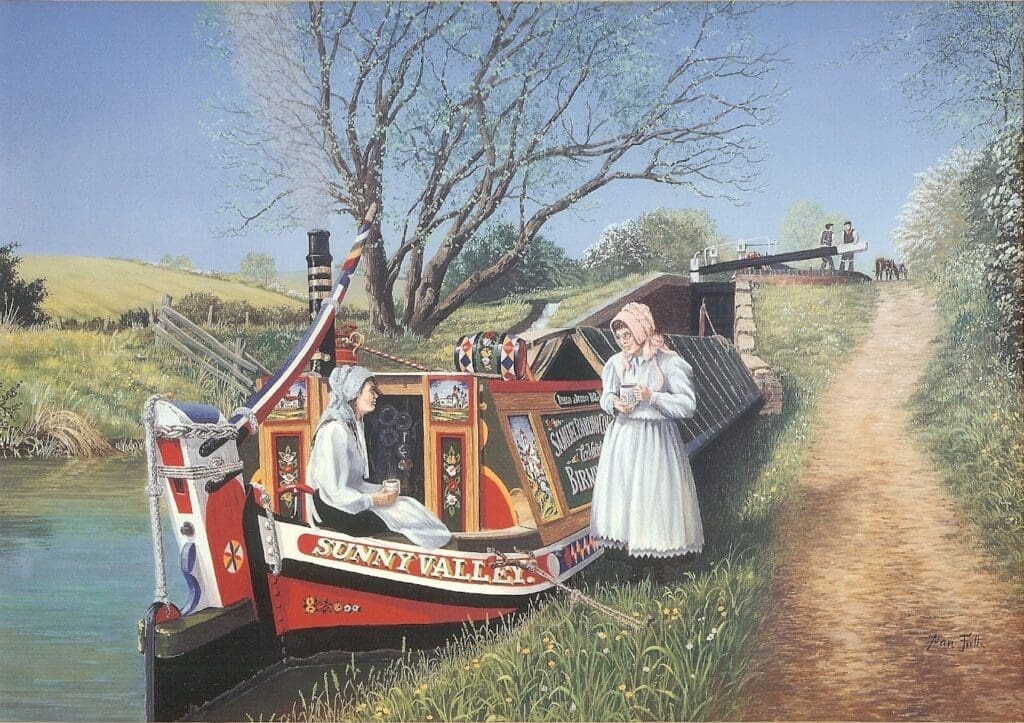

The painting is simply called Sunny Valley – Stratford on Avon Canal, as its main subject is the famous Samuel Barlow butty Sunny Valley. The butty was used in the wartime propaganda film Painted Boats, and is seen here below the lock, in all its glorious, traditional livery. It is still the seemingly happy, carefree days of the working boatmen – another world from today. Two boatwomen in traditional dress are chatting and enjoying cups of tea. Beyond up on the lock, their husbands are conversing while waiting for it to empty. There is a butty in the lock just visible and coming down, and in the distance the two horses are grazing peacefully. It is the passing of these boats, held up for a few minutes by the emptying lock, which makes for this social occasion. It is a bright, spring day, the towpath is alive with early yellow flowers, and its hedge is ablaze with white blossoms. God’s in his heaven, and all’s right with the canal world!

Alan has used his artistic licence to the full. The Samuel Barlow boat had a previous name and only adopted Sunny Valley for that film made in 1944, by which time the boatmen had long discarded traditional dress. And under whatever name, the boat probably never went near the South Stratford Canal. Finally, there is Alan’s hatred and fear of painting people. Eyes were his worst nightmare, and to get round this he would put people into heavily rimmed spectacles of the type a boatman would not have been seen dead in. But here the boatwoman is contentedly wearing large Nana Mouskiri-type glasses beneath her traditional pink bonnet.

Terry Stroud commented that despite all of this – which could have left Alan open to ridicule – the painting was a great favourite with the canal enthusiast and has been reproduced many times as prints of varying sizes, table mats, and greeting cards, some of which found themselves into frames to be displayed in boats. “Alan was first and foremost a fantastic artist, whose distinctive style, which he developed, could warm to many. Few artists achieve that.”

Terry had a point. In the Easter run-up in about 1992, Alan called at our marina shop to deliver a mixture of his stock we had ordered. I commented that I had been to see Sunny Valley the day before for the first time to give a valuation, as the then owner, who had spent a fortune restoring it was now thinking of selling it. Alan went back to his car and brought in a framed greeting card version of the picture, which he then gave me. I so liked it that it has been on the wall above my desk ever since. In the depths of winter, it has a special appeal. Some years ago the Inland Waterways Association described Alan as ‘probably Britain’s best known waterways artist’ – it was a sentiment I could endorse.

Alan was born in Blackpool in 1933. As a boy during the war, he became well-acquainted with the Leeds and Liverpool Canal at nearby Wigan. He told me that he would often help those boatmen who, due to call-ups, had been reduced to working single-handed to travel the lock flight. “If we could brew them a mug of tea, we were very welcome and we often stayed for quite a journey. I consider myself fortunate to have seen the final years of the working boats. Now I am painting my memories, and I rarely paint present-day canals.”

Alan completed his artistic training near Manchester, at what is today the Salford School of Art and Design. Here, a formative incident occurred. He was invited to visit L S Lowry’s small, terraced house in Salford with a group of students. He once told me: “Lowry was a very introverted and difficult man. I remember, as we arrived, watching him through his window as he went round his canvasses putting price labels on them in case one of us impoverished students wanted to buy one! The largest were £60 – a bargain, you might say, as they go for hundreds of thousands of pounds now – but that £60 was half a year’s student grant.

“Sadly, I knew one day they would be worth a fortune, and I regret it to this day. But what I learned from Lowry was invaluable. He set out to be an artist in the fashion of the day and failed miserably at it, so he decided to do his own thing and stick to it. It worked for him – and it’s worked for me. People still question whether he was an artist, as they do about me. I just call myself a painter, and a canal one at that.”

To pay for his life as an artist, Alan had also trained as an art teacher. In 1960 he moved to Coventry to become art teacher at the Tile Hill Wood School, where he continued to teach until ill health made him take early retirement in 1983. This was due to his continuous exposure to a minute, undetected leak in the art department’s gas heater which caused him lung damage and left him permanently short of breath.

During this time, his first marriage to Joy failed, ending in an acrimonious divorce. They had had two children, a son, John, and a daughter, Sarah, who is an artist. In 1975, Alan remarried to Anne, a maths lecturer at Hereward College in Coventry. Because they were both now aged in their 40s, they decided to adopt a pair of half-sisters, Sally and Teresa, aged five and two-and-a-half respectively, who had been taken into care. Alan used to refer to them as ‘the twins’ as they arrived on the same day. The new arrangements proved to be an immensely happy one, and in their respective declining old ages, a rewarding one to their adopted parents.

Alan used his time in Coventry to continue his exploration of the canals to the north of the city, and to paint them, in which he began to build up something of a reputation. In an interview in 1981, he said: “I met the late Joe and Rose Skinner on their boat Friendship at Sutton Stop. One of my great pleasures was spending an evening drawing on their boat and talking about their life on the cut.” But strangely, although Alan probably joined others going boating here and there – how else could he have acquired his extensive knowledge of the waterways? – he never owned a boat, nor even went on a hire boat holiday, which the young ‘twins’ were always begging him to do.

Once retired, Alan now threw himself into his art. To make it pay, he began publishing prints and greetings cards of his popular paintings, doing his own framing in his bungalow loft which he had converted into a workshop, and doing the rounds of canal shops and attending waterway rallies. He had long before turned the far end of his sitting room at the back of their house into his studio. He bought the house because it had a large, modern window giving good views to the north, into open countryside. There was a valley immediately below and rising ground on the far side, which included two fine chestnut trees on the rising slope which he included in his paintings whenever he could – a sort-of signature. Lowry once commented: “If people call me a Sunday painter, I’m a Sunday painter who paints every day of the week!” That was now Alan’s life.

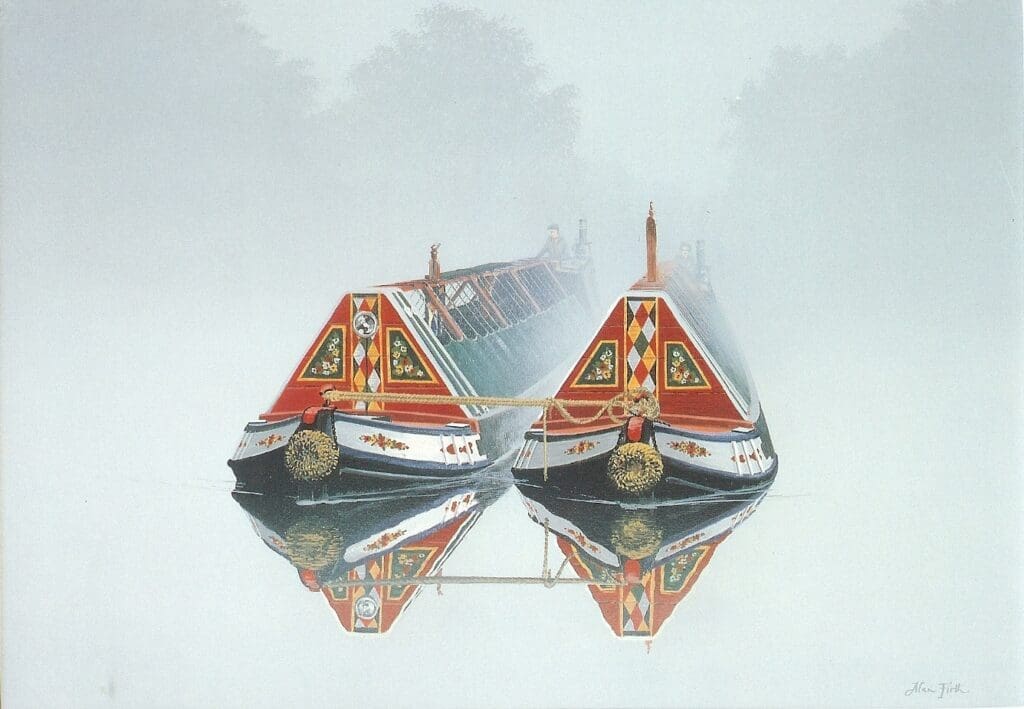

Alan’s chosen technique was to paint in gouache, a thick water-based paint which dried quickly. A favourite tool he mastered to perfection was using an airbrush, which allowed him to create misty effects. His problem was that he struggled to finish and let go of a work. He was always dissatisfied, and in consequence he never had any of his works on display in his house.

Terry Stroud recalled that he had once attended a rally at Moira Furnace on the Ashby Canal, where he had a stand. Walking around, he spotted a canal society stand that was selling off one of Alan’s original paintings very cheaply because it had suffered some water damage; the owner had given it to the society to on-sell. The painting was probably the largest Alan ever did. It was a classic Firth – a working narrowboat somewhere on the Leicester Line, passing under a canal bridge at night with the moon rising through the bridge-hole. That moon, the left-hand side of the bridge, and the water flowing down to the left-hand corner all had watermarks of varying degrees. Terry later took the painting to Alan when he was going to see him at his studio, and Alan said he would repair it there and then. The moon was no problem, and quickly sorted, the watermark to the bridge was painted over with ivy, and then Alan airbrushed and redid the water – just like that. When he had finished, Alan commented: “I never liked the way I did the water in that picture. I’m glad you brought it back.”

I acquired Braunston Marina in receivership and in a rather sorry state in 1988. We formally reopened in the spring of 1989, including making the old rope shop into a shop selling chandlery and a mixture of canal items. My then general manager, who had been with the company before I acquired it, knew Alan of old – as I did not. He was a great enthusiast for Alan’s canal-ware range and wanted to make something of a splash with it for the formal opening of the shop. It was to be done by former working boatmen Jim and Doris Collins, now working for me. This we did and in so doing I first met Alan, and over the years perhaps got to know him as well as anyone else involved with the canals. I always enjoyed chatting to him when he came in to deliver his stock and finding out what paintings he was working on.

In 1991, I started the Braunston Boat Show with Simon Ainley, the dynamic manager of British Waterways’ Braunston office, with whom in many ways we were able to achieve so much. The event proved a runaway success that grew rapidly. Each year we built on the previous year, adding new attractions. Among the staff of British Waterways Braunston office was Helen Harding, the local publicity officer. She was also a trained artist and member of the Guild of Canal Artists. This was an organisation founded in the 1980s by a group of artists who were also waterways enthusiasts, with Alan Firth a founder member.

British Waterways made 1993 nationally into the big year for the canals – the bicentenary of 1793, the year of Canal Mania, when most of the acts for new canals were passed through Parliament. As part of these celebrations, Helen suggested that the Braunston Boat Show should sponsor a marquee for the Guild of Canal Artists in its office car park, which we did with very encouraging results. I cannot recall one of the well-known artists of the time who was not there. It was a veritable feast of canal art.

Alan, of course, was there very much to the fore, smiling and in good form, as besides his usual canal-ware, he had recently landed himself with a jammy prestigious contract with Wedgwood. This was to make eight canal paintings, collectively to be called Waterways By Winter Moonlight, which would be reproduced on eight-inch round wall plates. These would then be sold as collectors’ pieces. Wedgwood did a lot of that sort of thing at that time, their collector leaflets being a standard insert in Sunday newspaper colour supplements. People could subscribe for the set, to be issued one at a time over a period so they could be paid for in instalments. The first one was now out, entitled Between The Locks, with the blurb proclaiming it ‘an evocative new collector’s plate inspired by a living part of our heritage that harks back to an age greater than our own.’

On Alan’s stand was an example of that plate, and with it, and very much bigger – about eighteen inches in diameter – was his round painting for that plate. It was my first encounter with Alan together with an original of his works, and we had a long and enjoyable talk about it. Alan told me he had used a photograph of former working boatmen Jim and Doris Collins, whom I now employed, approaching Lock 2 on the Braunston Flight.

The photograph, taken in 1961, came from Mike Webb’s great booklet collection of photographs called Braunston’s Boats. Alan had used his artistic licence to set the scene by moonlight, in thick snow. The boats are breasted up, and Doris is snug below in the cabin, one assumes making the evening meal, while Jim steers on into the night. Who was going ahead to open the lock is not made clear. Ugly 1960s add-ons to Braunston have been removed. Instead, there are substituted Alan’s beloved trees seen from his studio window. Alan told me he retained the selling right to the eight paintings, once the whole plate selling saga was over, and offered the painting to me for £750 on this basis. At the time, I and the marina were up to our necks in debt, and I turned down the offer. It was one I have always regretted – like Alan with that Lowry.

- Next month: In part two, Tim eases that pang of regret – and goes on to commemorate Alan Firth in very special ways.